Bulgaria's Forgotten Schools: Milanovo Village

- Елена Татарова

- Jun 2, 2021

- 8 min read

I’m on the bus’s front seat and I can see my teacher - friends in the rearview mirror. Kaloyan is always quiet and looking anxiously out the window. I’m sure that his mind is going fast, maybe planning a lesson or a unit, that he works even in his sleep. Maria is sleeping, snugged like a cat and I think a whole life of knowing her won't be enough to get to know her. She is an enigma, which combines unwavering determination and responsibility with a child's imagination and mentality. Gabi is in the clouds because she carries the heart of a poet. Contemplation and insight, along with tireless care to help, make her perhaps the best person I know. I am sure that Yanko looks at the landscape and imagines how millions of years ago the Vratsa Mountain rose, cut by the river Iskar, to create these bizarre shapes that we see partly from the broken fog. I am also sure that he can imagine the formation of fog, clouds, and everything that surrounds us on this day. This is his geographical superpower. I love to travel with my friends because it allows me to discover their world and other worlds, giving me courage in the face of the unknown.

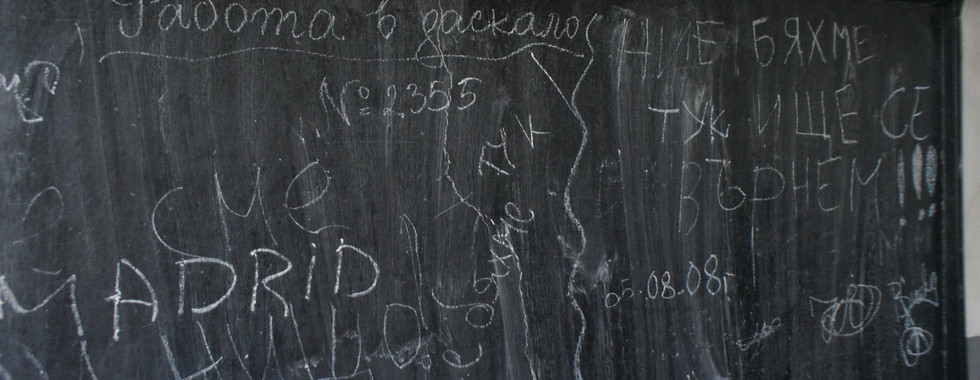

The gorge of Iskar cuts us deep into the mountains, and the Balkans engulf us in their arms. We soon find ourselves in the village of Milanovo. There is something mysterious and mystical in the air and the location of this village perched on the edge of the cliff. The school is no different from the previous ones, part of this series. And here oblivion and the feeling of mortality reign. Only here, however, have we found a life that is not only a witness to history but its creator and guardian. It is about this life that would like to tell.

Gabi and I go in search of residents on the streets of Milanovo. Because it's Sunday noon, only our footsteps can be heard in the streets. We have nostalgic conversations about rural smells and how they refer us to childhood memories full of color, games, fried breakfast mekitsi, cherries, donkey carts, winter food, and the hands of our grandmothers, who seemed to be able to do anything. Gabi is my favorite company in nostalgia. From one of the houses comes the barking of dogs and the chirping of chickens. We see (as we will find out later) Draga Borisova leaning over her flowers. We tell her quickly what I'm here for, and she happily replies that she knows the right person to tell us the history of the school - her good friend Tsvetana Dinova, longtime director of the school. Draga immediately called on the phone and told her girlfriend about "these children" who want to learn more about the school in Milanovo. And even though we are in the second half of our twenties, we quickly return to our childhood, following Draga through the streets and listening to her story.

"I am a daughter-in-law here, otherwise I am from the Tran region, from Buhova, right on the border. Not a single person remains in our village in the winter. I'm better off here, there's no life there at all. I love this village very much, I had three children here. ” I ask her if there are children in the village and how many of them go to school. "There are three children who go to school in Lakatnik. Otherwise, we have a lot of small children up to 1-2 years old. Many were born alive and well. We even have twins and triplets.”

Two things make a strong impression on me in the way Draga speaks - one is that her name suits her (Draga means dear), and the other is the general feeling and protection that flow from the word "we have". Only here in the village does a woman accept everyone as her children.

We cross the threshold of Tsvetana Dinova's home, and she greets us warmly and with a smile. Draga also openly greets her and asks if she remembers her. Their friendship is almost fifty years old. Tsvetana's house is warm, cozy, and smells of tea. Seedlings are arranged on the tables and chairs in anticipation of sunny weather. She lovingly shows us her peppers, tomatoes, brussels sprouts, and even kale. In the next hour and a half, this house will become our home, where we warm up, dry our hair from the rain, and want to visit again from now on.

I feel more and more like a guest at my grandmother's - Tsvetana and Draga are starting to fuss about how to provide us with maximum comfort and what to offer us for eating and drinking, not because we are guests, but because they welcome people with good and generous nature and you immediately feel close. All their fuss about making coffee is accompanied by friendly sarcastic hints.

Tsvetana: "Open the stove to warm up."

Draga: "I'm not going to open the stove, it's warm. I’d open it and break your stove and then you’d have to fight me, comrade Dinova."

Tsvetana: "She always calls me 'comrade', and what a comrade I am..."

Tsvetana starts making us coffee and takes something from the cupboard behind Draga.

Tsvetana: "Wait, my dear, my coffee widget is behind you."

Draga: "Now you try to pick me up."

Tsvetana: "Let me give you a chair, taller, to sit comfortably."

Draga: "Just put on the coffee and don't explain yourself to me."

Tsvetana: "Come on, darling, pour the children coffee."

Draga: “Here, one day I should come and you use me as a waitress. I don't think I divided it equally. Here's to the smallest, the least "- and hands me a glass.

Tsvetana: “So she is to blame, not me. I give to everyone equally. ”

Then Draga, as a "specialist", was ordered to open up and treat us to Mirazhki. As I watch them treat each other, I have the feeling that the whole shared history and value system of this village is locked in their friendship.

Tsvetana begins her story as a skilled storyteller and author of three books.

"I don't go to school anymore because I'm going to have a heart attack, but its name is 'Father Paisius.' There were two schools - one of them was called "St. St. Cyril and Methodius”, and the other was called, let me say it in the past perfect tense - “Father Paisius”. With this sentence, she indirectly answers my question about what she taught. Only a Bulgarian language teacher divides the past into past perfect and past tenses. The history of the village of Milanovo or as it was called before - Osikovo, she has collected in her books and given her life to, although it remains unfinished.

"Since the middle of the 19th century, there has been a school here, a cell school, like the ones from the Renaissance. This means that people used to be curious and interested in this problem. They found a way with textbooks, albeit primitive, to teach reading and writing. A scholar at the time was the one who could read and write. You didn't need any special education to become a teacher, you just had to be literate.”

"After the Liberation, the people of the village seriously thought about a school, because so far they had studied in private houses - so imagine below is the pub, and above is the school, which is not comfortable and decent, but still it was a solution to the problem." In 1879 in the Supreme National Assembly there was an MP from Osikovo - Ivan Stoyanov Runchev, who went with the big order to build a school in the village, because there were students, there were teachers, but no building. Later, the school building was chosen as Torman's house. Tsvetana shares “my mother-in-law studied first and second grade there. She taught my little son Yavor to read before he went to school. The woman with a second grade. I praise her, not my son.”

At the beginning of the last century, the village began to grow and spread to the south, which necessitated the construction of a new building in 1922. "I remember it, but I didn't study there because the third building had already been built. It was located where the canopy of the Vratsa Balkan National Park is now. But there are still plum trunks that were next to the schoolyard fence. And when I pass it, I keep looking at them and remembering them. " The first two buildings have been demolished and only the third is currently left. ”One was deliberately demolished to make way for the central square. The other one began to crumble and gradually people took the bricks, some took stones, and termites cut it up and it disappeared."

“The construction of the third building is very interesting and long. First, a place had to be determined and the Topaliiski brothers donated their meadow for the new school. Construction began before September 9, 1944, under Mayor Tsvetko Alexandrov, when the foundations were laid and the basement dug. After September 9, hard work began to complete the building, in which the whole village participated. A brigade movement was organized in three shifts of 45 days, in which young men and women worked. Even the priest was a foreman in all three shifts because he worked on the fittings - bending and forging the iron for the school. They made bricks, drove sand, carried stones, cut down trees, and drove them with oxen, dividing them on the spot - and so in a very short time, less than two years, the roof was laid. There was a woodworking and metalworking workshop, a canteen, a gym, a boarding house, and a school bus. All this evokes in my mind a picture that I suppose is relevant for many villages - a warm spring day, joint efforts, shared, hectic work, and a school ideal.

On February 6, 1951, the school opened its doors. "I remember that date. They didn't even wait for the end of the school year, just to enter this new, big building and study. With a lot of volunteer work, since they didn't have money, but they worked hard and made their bricks, which is commendable.” There is great excitement and pride in Tsvetana's voice about something creative, something meaningful, a product of solidarity, which not everyone can witness in their life. Tsvetana became a Bulgarian language teacher at the school after being the director of the kindergarten, and later graduated in Bulgarian Philology, became a mother of two children, and together with her husband built their home in Milanovo. She remained a teacher for less than two months before accepting the position of a principal.

"It is difficult for me to talk about that moment. The former principal made an excursion vacation for a group of students from the school to Vidin and went to see the river. One of the children secretly took diving fins for their feet and secretly put them on and jumped to swim. Unfortunately, he drowned. The director was with them. He was later fired. So instead of being a teacher, they offered me a principal and those above decided to approve me. " Tsvetana was the director of the school for 21 years until 1997. Under her leadership, there were 176 children in the beginning. ”But with each passing year, the number of children decreased, decreased, decreased, and finally we started merging classes. And the worst thing is to teach two lessons - for example, you have a story - you teach one story to some, another to others. This boy Biser, a very smart child, went on to study history at university. I gave him an assignment for one lesson, and he listened with one ear to the upper-class lesson and answered all my questions about both classes.”

The school was closed in 2000 due to a lack of students. "If something had happened to my house, I would have gotten over it somehow. But for that building there, it's much harder for me. The depopulation of the villages was a trend, it was terrible, even though there was work for the people, there was production. And the people who worked here gave birth to their children here and they studied here. And all this was completely destroyed. If Attila's Huns had passed from here, they would not have destroyed it as cruelly as our native Bulgarians."

Tsvetana's words strike me with sadness. At the same time, it is clear to me that nothing is eternal, neither the school, nor Attila, nor us. In this world of transience and destruction, however, 21 years as a principal in a school, among children, smiles, learning, and love, seem to me like an eternity full of meaning.

Text: Elena Tatarova

Photography: Yanko Morunov

Translation: Marin-Assen Kodzhaivanov

Comments